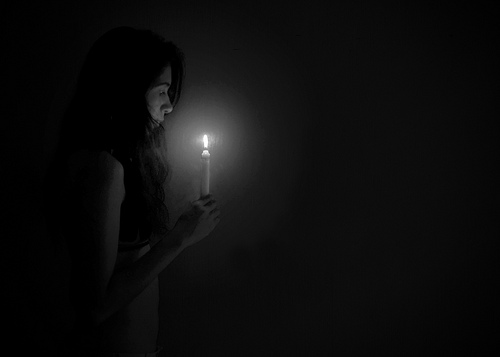

“May it be Your Will, Eternal One, our Almighty God and Almighty God of our ancestors, that You stand us in a corner of light and do not stand us in a corner of darkness. And may our hearts not become sickened and may our eyes not become darkened.”

(Talmud, B’rakhot 17a)

These are very dark times for anyone who cares about life and decency, in our own country, in Israel, and in the world. The news is terribly depressing, in an overwhelming way. The tragedies we experience are heartbreaking, whether we focus on the stories of individuals or of masses of humanity. The political issues seem to have no easy solutions, except for people who have abdicated all responsibility. The moral challenges are formidable and almost as frightening to face as the terrors aroused by the heartless, murderous terrorists whom we have not succeeded in stopping or overcoming. Dwelling on all of this, we feel our hearts become sickened and our eyes grow dark.

Yet, we go on with our routines, as we should. Our day-to-day lives, our jobs, families and all our immediate concerns occupy so much of our energies. As so many have pointed out, there is a measure of simple heroism in the maintenance of our ordinary world. But we must ask ourselves hard questions: How much is our commitment to living our lives as if nothing is the matter a noble choice and how much is it an evasion? We must ask how much attention we will give to the problems surrounding us and how much we will ignore them. As we react to these crises, how much energy will we invest in ruminations and proclamations that, however passionate and self-affirming, are really pointless, at best, or, worse, serve as substitutes for meaningful action, or, worst of all, promote attitudes and choices that block any possibility of bettering our world?

The routine I have established for myself for this column is to follow a monthly traversal of the Morning Service, its prayers and their meanings. I am grateful for the sense of security that such a routine offers. Yet, I am not oblivious to the strain under which we live at present, at this moment of moral and spiritual challenge. That sense of strain cannot but color my thoughts as we move to our next prayer. We have arrived at the main prayer of all, variously known as the “`Amidah” (The Standing Prayer), “Sh’moneh `Esreh” (The Eighteen Blessings), or, simply, “Ha-T’fillah” (The Prayer). When an individual recites this prayer it is recited silently. When a minyan joins together this prayer is also offered on behalf of the entire community and then, of course, it is recited aloud, for all to hear.

This “prayer of prayers” follows, in our morning service, on the heels of the blessing that praises God as the One Who has redeemed Israel – ga’al Yisra’el. We are meant to remember that God has come to our aid in our most desperate moments. With that memory of a caring, responsive God freshly recalled, we stand before God to offer our personal and communal prayers.

It was so important to our Sages that this linkage be effective that they insisted that no one interrupt the flow between the end of the blessing “ga’al Yisra’el” and the beginning of the `Amidah – for any reason, in any way. No announcements should be made, no greetings or “gezundtheit” wishes, and no “amen.” We are to move seamlessly from the recollection of our exultant song at the Red Sea to utter silence. We are to fix the image of God as Redeemer firmly in our hearts as preparation for opening our mouths in genuine prayer.

How shall we begin? How can we hope to begin? What words or expressions can possibly be adequate to this moment? The traditional `Amidah offers a script. The script can be followed closely or loosely, but it offers a guide to help us structure our audience with God.

We begin with the first blessing. The idea is to start with words of acknowledgment as a means of introduction; “Barukh atah… – You abound in blessings, Eternal One, our Almighty God and the Almighty God of our fathers and mothers…” We acknowledge God, before whom we stand, and we acknowledge our ancestors, whose merit has gained us entry into God’s Presence. It is thanks to them and their spiritual legacy that we do not have to stand before God naked and unaided.

What is the nature of that spiritual legacy? What about the ancestors was so special that God stood by them and with them, establishing a covenant that is our sacred inheritance? We could conceivably choose many qualities and attainments of our ancestors. So many of them are documented in the Torah portions we read during these weeks. But our blessing distills their attainments into only one phrase: “hasdei `avot v’imahot – the loving acts of our fathers and mothers.” We do not celebrate their heroism, their righteousness, or their belief in God. We celebrate their evincing of love – hesed –hasadim.

This is what God remembers about them. And this is what we are meant to remember about them as their descendants and heirs. As we begin our prayers we are meant to remember our capacity to act lovingly. The first blessing wants us to realize that our capacity to act lovingly is our beginning and our end; it is our calling card and it is the key to our redemption. It is the tiny corner of light in which we might hope to stand. In this dark hour we need to remember this more than ever.

Image by Yashna M  used with permission via Creative Commons: Attribution License

used with permission via Creative Commons: Attribution License

- Toby Stein: In Memoriam - Thu, Feb 8, 2024

- Faithfulness and Hope: Parashat Sh’lach - Thu, Jun 23, 2022

- Past Their Prime: Parashat B’ha`a lot’kha - Thu, Jun 16, 2022