Parashat Yitro

Exodus 18:1 – 20:23

Over the last couple of years I have been struck by the special nature of the first half of our Torah reading, pondering the special message of the record of Yitro’s gift to the Jewish people. I have discussed how important it is that we appreciate that the Torah – God’s Instruction – has elected to incorporate within itself the democratizing lesson of a human being, and one who was not even part of the Jewish people. (See Torah Sparks 2016 and 2017)

I want to add just a little bit more to those musings. Yitro, a Midianite priest, sees his son-in-law, Moses, administering God’s Law to the demanding populace. He tells Moses that this is not the way. Moses and the people will collapse under the stress of such a centralized system. Moses must spread the power to any worthy Israelite and share the mission of spreading the Torah with them. This is a democratic revolution brought about by our – and God’s – acceptance of the ideas of a non-Israelite outsider.

What strikes me today is the paradox of comparing Yitro’s intention with our own subsequent reception of that intention. Yitro hoped to make life easier for Moses and for all of Israel. Moses would not have to shoulder the burden alone. And the Israelites would not have to suffer the long delays in administering justice that come from a centralized, bottleneck-inducing system. But Yitro’s hope to make things easier for us has actually confronted us with a challenge that seems to have made things more difficult, not less.

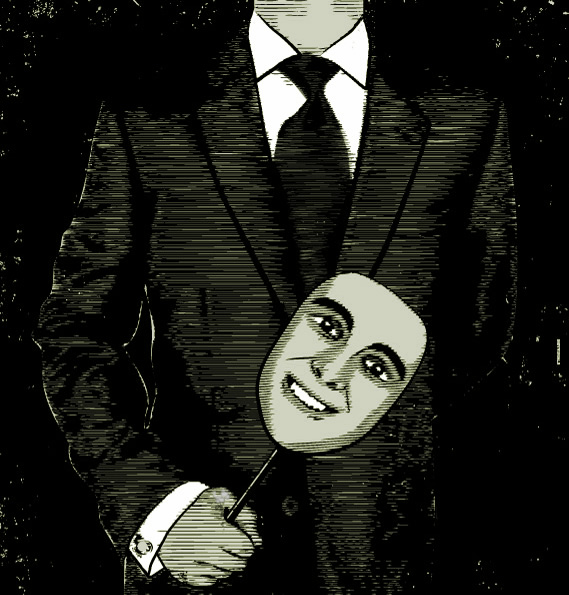

We struggle to embrace democracy. These days, in the USA, in Israel, and around the world, we see how hard it is for the people to accept democracy as the correct path for self-governance. Populism, instead of pushing for democracy, pushes for authoritarian centralization of government in the hands of strongmen who do not respect the Other. Nondemocratic ideologies of suprematism – of any form – seem to be easier for many of us to adopt.

Indeed, it is no coincidence that the idea of democracy is introduced in the Torah by a person who is Other to our people. It is crucial to come to terms with the fact that it is Yitro, a Midianite priest, who teaches Moses the lesson of democracy. (The midrashic fantasy that Yitro converted to Judaism should be recognized for what it is, the fantasy of an oppressed people who found it hard to imagine a worthy Other.) For democracy is not to be reduced to a system of majority rule. The foundation of democracy is the notion of universal human rights, possessed by everyone, including – especially including! – those who are not like the majority.

Oh Yitro! You sought to make it easy for us, but you have actually made it so hard!

One of the ways we try to resist the lesson offered by Yitro is to claim that it is a value alien to (our) religion. Many religiously devoted people, of all three monotheistic religions, have begun to chafe against the idea of democracy and label it a secular assault on religion. It is therefore imperative to remember that the Torah has incorporated Yitro’s message and sanctified it. To be true to God’s Torah is to do the hard work of opening one’s self to the Democratic Challenge.

Why is it so hard to embrace the Other? Why is it so hard to embrace the Torah’s teaching that our Otherness to “each other” is made possible precisely because we share a universal essence: We are all God’s children, each uniquely created in God’s Image?

But Yitro’s lesson is the hard truth. If we will not accept it, then “You and this people with you will surely wither away.” (Ex. 18:18)

Shabbat Shalom

Rabbi David Greenstein

![]()

Subscribe to Rabbi Greenstein’s weekly d’var Torah

image: “Facism” © PetrosV altered and used with permission via Creative Commons License

- Toby Stein: In Memoriam - Thu, Feb 8, 2024

- Faithfulness and Hope: Parashat Sh’lach - Thu, Jun 23, 2022

- Past Their Prime: Parashat B’ha`a lot’kha - Thu, Jun 16, 2022