Torah Sparks

Torah Sparks

Exodus 10:1 – 13:16

This Torah portion brings us to the climactic event of the exodus of the Israelites from Egypt. This event is so central to our story and identity as a people that much of our tradition is self-proclaimed as “a remembrance of the Exodus from Egypt – zekher li’y’tzi’at mitzrayim.” So let us note how the Torah chooses to tell of this event.

If we take the notion of the exodus at face value we should expect the story to be about our actually leaving Egypt, our “exodus.” Yet, the action of the Israelites physically walking out of Egypt is given very few verses in our text. Generously considered, the exodus event occupies verses 31-41 of Chapter 12, perhaps 11 verses in all. Far more attention – more than ten times as many verses – has been given to narrating the story of the plagues. Furthermore, we should notice, in addition to the Torah’s choices about what to narrate and how, also its introduction of a new focus to its communication. This Torah portion is the first one in which the Torah turns from a voice of story telling to a voice of law instruction. In all of the Torah up to this point we traditionally count a total of three commandments. In this Torah portion we can count twenty.

The few verses that tell about the exodus are sandwiched in between many verses of law, the laws of the observance of the Passover ritual in Egypt and beyond, of the sanctity of the first-born and of tefillin. These verses form much of the basis for our continued observance of Passover, including the seder, during which we retell the story of the exodus. So, again, what does this story entail? If we really pay attention we notice that we are not commanded to reenact our walking out of Egypt (various play-acting practices notwithstanding). Instead, we are commanded to reenact various elements from the first Passover seder – which took place before our exodus, while we were still in Egypt!

It emerges that the act of leaving Egypt is overshadowed by other concerns that are apparently of more importance to the Torah. The fact that we walked out of Egypt as free people is of less moment to the Torah than that, paradoxically, though we were still officially Pharaoh’s slaves, we accepted upon ourselves – right under the noses of our oppressors – a set of laws and rituals that spoke of our confidence in a protecting God of Freedom. What is important to the Torah is that we accepted upon ourselves, in the midst of a night of terror and anxiety, a commitment to follow those laws with scrupulous care. It is these rituals that we are to perpetuate. They form the basis for our handing down the story from generation to generation. And the story they reenact is not the story of our walking away from Egypt; it is none other than the report of that first act of commitment. What we are called to remember – y’tzi’at mitzrayim – is not the exodus from Egypt, but the exodus that happened in Egypt. Some would put it that we are commanded to celebrate the exodus of Egypt from within us.

Shabbat Shalom

Rabbi David Greenstein

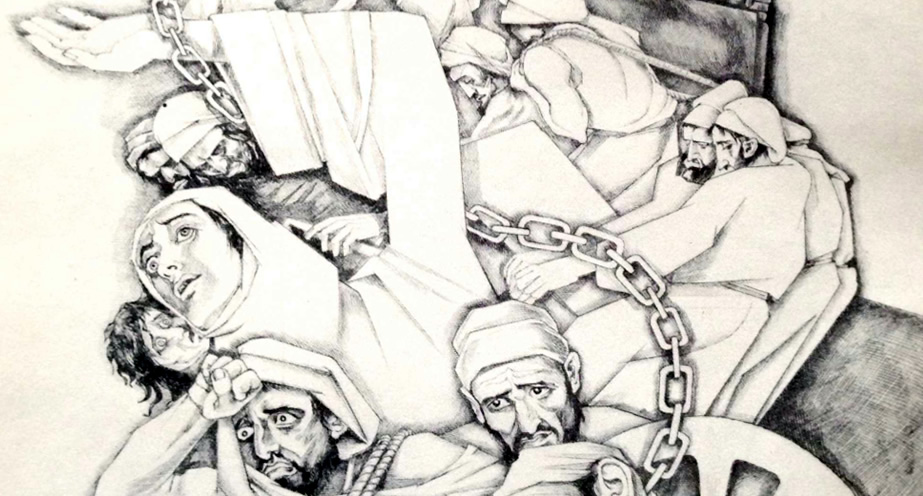

Image: “Because we were slaves unto Pharaoh in Egypt”, Saul Raskin Haggadah, 1941.

- Toby Stein: In Memoriam - Thu, Feb 8, 2024

- Faithfulness and Hope: Parashat Sh’lach - Thu, Jun 23, 2022

- Past Their Prime: Parashat B’ha`a lot’kha - Thu, Jun 16, 2022