Parashat Mishpatim

Exodus 21:1 – 24:18

Freedom can be frightening. Our Torah portion considers various scenarios in which freedom can arouse fear. Surprisingly, the Torah can imagine that a slave may refuse to be set free. Apparently one may be afraid of the prospect of one’s own freedom. (Ex. 21:5) Perhaps it is this most basic personal fear that underlies the more common phenomena, where it is the freedom of others that we find threatening.

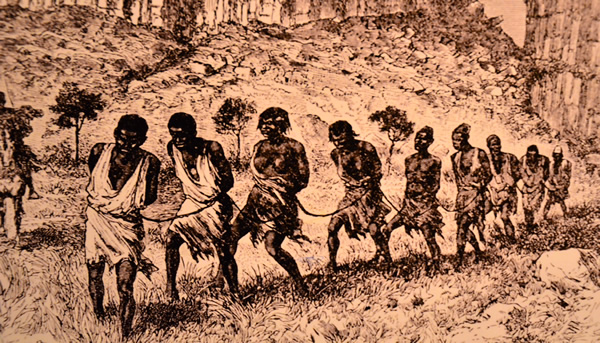

Much of human history is about the efforts of some humans to limit or destroy the freedom of other humans. One pure form of this syndrome is slavery. Whatever economic or sociological explanations are given for the endurance of slavery as a human reality, one very fundamental driving force behind this horror is the fear and anxiety we may experience in the face of other people’s freedom. Tragically, overcome by fear of the freedom thrust before us, we seek to subdue it and erase it, to shackle it and enslave it.

As much as we moderns would wish that the Torah had prohibited slavery outright, it did not do so. (See some discussion of this in Torah Sparks, 2015.) The institution of slavery – the very status that we were saved from by God when we were extricated from Egypt – is accepted by the Torah as a practice of the Hebrews. The abuse of one human being by another is still possible in its legal system, but the Torah makes some progress in softening the practice and limiting it. Thus, for instance, if a master beats his slave too much, the very quality that provoked such cruelty – the master’s fear of the free nature of another human being – is punished by the Torah’s command that the master must grant the slave total freedom. (Ex. 21:26-27)

Our fear of the freedom of others does not always get expressed in the ultimate oppression of enslavement. We engage in lesser forms of oppression when we have the power to do so. The stranger, or alien (“ger”) is a particularly poignant example of someone whose strangeness and marginal status highlight for us the problematics of his freedom. The ger is not quite subsumed within our system (- enslaved), but remains a free foreigner. Therefore she makes us uneasy and afraid. We are prompted to respond with cruelty. So the Torah warns us a number of times in this parashah – and will continue to do so throughout the rest of the Torah – not to oppress or behave badly toward the alien. (Ex. 22:20 and 23:9)

Here, in contrast to the case of slavery, we find an outright prohibition. Why the difference? Another difficulty is that the prohibition against mistreating the stranger is often connected to our past experience in Egypt. But it seems strange that our enslavement in Egypt does not serve as the basis for an absolute prohibition against enslaving others. Rather, our past experience as foreigners in Egypt – a far less salient feature of our history – is appealed to repeatedly as the basis for the Torah’s command to deal decently with the foreigner. Our recollection that we were freed from slavery, a constant refrain in our tradition, does not create the basis for abolishing slavery, while the dim memory of our being alien sojourners in Egypt serves as sufficient grounds for outlawing sojourner abuse. Why the difference? But perhaps that is how the Torah wishes to lead us forward.

We must remember that we were free aliens in Egypt before we were enslaved. The Egyptian oppression began out of their fear of us while we were still free aliens. Enslavement followed. We must remember this so that we may learn not to capitulate to fear. Thus, hopes the Torah, if we can first accept that the freedom of a stranger does not threaten or limit our own freedom, then we may become secure enough in our freedom to relinquish the fear that leads us to enslave others. The abolition of that fear would be the abolition of slavery itself. But we have yet to abolish it.

Shabbat Shalom

Rabbi David Greenstein

![]()

Subscribe to Rabbi Greenstein’s weekly d’var Torah

Image: “Slaves in chains being taken to be transported to the Caribbean” by Ben Sutherland is licensed under CC BY 2.0

- Toby Stein: In Memoriam - Thu, Feb 8, 2024

- Faithfulness and Hope: Parashat Sh’lach - Thu, Jun 23, 2022

- Past Their Prime: Parashat B’ha`a lot’kha - Thu, Jun 16, 2022