Editor’s Note: Rabbi Greenstein gave this sermon on Yom Kippur 5778 (Sept 2017).

Editor’s Note: Rabbi Greenstein gave this sermon on Yom Kippur 5778 (Sept 2017).

So, a rabbi walks into a cave.

With his son.

The son says to his father: “Abba, Father, can I get you anything?”

And the rabbi says: “That’s alright. I’ll just sit in the dark.”

This joke is inspired by a story in the Talmud (BTShabbat 33b-34a). It happened during the Roman rule over Palestine, in the middle of the second century CE.

The Romans had brutally put down the rebellion of Bar Kokhba. Along with the tens of thousands of Jews who lost their lives, the greatest rabbi of the era, Rabbi Aqiva, was tortured and put to death. The future of Jewish life in the holy land was under a cloud, while the Romans went about rebuilding the subdued country from its devastation.

And a few rabbis, all students of the martyred Rabbi Aqiva, were sitting and talking. With them sat another Jew, listening.

Yehudah, always first to speak, hesitated and groped for words: “You have to hand it to these people. They really know how to build roads. Their aqueducts are things of beauty. Their bridges are marvels. We have to give them that much.”

Yose said nothing. There was an uncomfortable silence.

Then R. Shimon bar Yohai – later called “Rashbi” – could not control his rage: “All their power they abuse for themselves!

Sure, they build market-places – so the harlots will have more customers; they build baths, to pamper themselves while they are surrounded by suffering; they construct bridges, to levy taxes and tolls to support their empire.”

Yehudah had tried to find something positive to say about the occupying power of Rome. We should notice that he does not choose to extol the vast entertainment industry of Rome, the famous “circuses,” that fed the ravenous appetite of the masses for staged violence, thereby deflecting their attention from their own abject oppression. No. He praises the projects that contribute to the commercial development and social hygiene of the people.

But Rashbi will have none of it. And he was not wrong.

His heartfelt protest against the deadly combination of selfishness coupled with great power is as important today as it was almost 2000 years ago. The perspective he denounced is alive and well in our world. How many today would appropriate legitimate concerns about our infrastructure needs for the purposes, not of creating a more livable society for all, but as a means to enrich those who already have tremendous power?

How many today would encourage massive development of our resources at the expense of the health of the people and the sustainablitiy of our environment?

How many today believe that the path to creating a successful economy depends almost entirely on not taxing wealthy people?

How many today find it hard to grasp that it is more important to protect lives than it is to protect the profit margins of shipping companies?

But Rashbi was not condemning the powerful and wealthy only for seeking their own benefit. He was appalled by their success in creating a culture, a civilization that encompassed the poor and the powerless, as well, that got them to buy into these false values as everyone’s values.

Our values are influenced by our environment. Constantly surrounded by commercialized images, we are silently being indoctrinated to see everything as a commodity. We start believing that the market must be free, but people – not so much. If everything is reduced to the terms of the market place, we all learn to prostitute ourselves.

The means of affecting people can be quite subtle. The effects are measurable. Nobel Prize winning economist and psychologist, Daniel Kahneman, talks about what happens to us as thinking and feeling human beings when we are exposed to even seemingly harmless stimuli. The process of being affected by these stimuli he calls “priming” and the stimuli are called “primes.”

He writes: “Reminders of money produce some troubling effects.”

He describes a number of experiments in which one group was “primed” with money-related stimuli, while the other group was not exposed to such primes. He writes: “[Some] primes were [quite] subtle, including the presence of an irrelevant money-related object in the background, such as a stack of Monopoly money on the table, or a computer with a screen saver of dollar bills floating in the water.”

What happens to people who are exposed, however gently and subtly, to these images of money?

Here is the good news: “Money-primed people become more independent than they would be without the associative trigger. They persevered almost twice as long in trying to solve a very difficult problem before they asked the experimenter for help, a crisp demonstration of increased self-reliance.”

But then Kahneman continues: “Money-primed people are also more selfish: they are much less willing to spend time helping another student who pretended to be confused about an experimental task. When an experimenter clumsily dropped a bunch of pencils on the floor, the participants with money (unconsciously) on their mind picked up fewer pencils.”

These are people who think they are being asked to perform other tasks, while the true experiment is to see whether they are being unconsciously influenced by symbols of money in their vicinity. Kahneman summarizes: “The general theme of these findings is that the idea of money primes individualism: a reluctance to be involved with others, to depend on others or to accept demands from others.

[These] findings suggest that living in a culture that surrounds us with reminders of money may shape our behavior and our attitudes in ways we do not know about and of which we may not be proud.” (Thinking Fast and Slow, pp. 55 – 56)

Professor Kahneman reports that these findings are often met with denial and disbelief by people. We dismiss them at our own peril.

Rashbi’s outburst was a conversation stopper. The group broke up and each rabbi headed home. But their words had been overheard. Soon the Roman authorities reacted. They decreed that R. Yehudah, who had praised the government, should be rewarded. R. Yose, who had been silent, would be exiled. But a death warrant was issued against Rashbi for daring to criticize the powers that be.

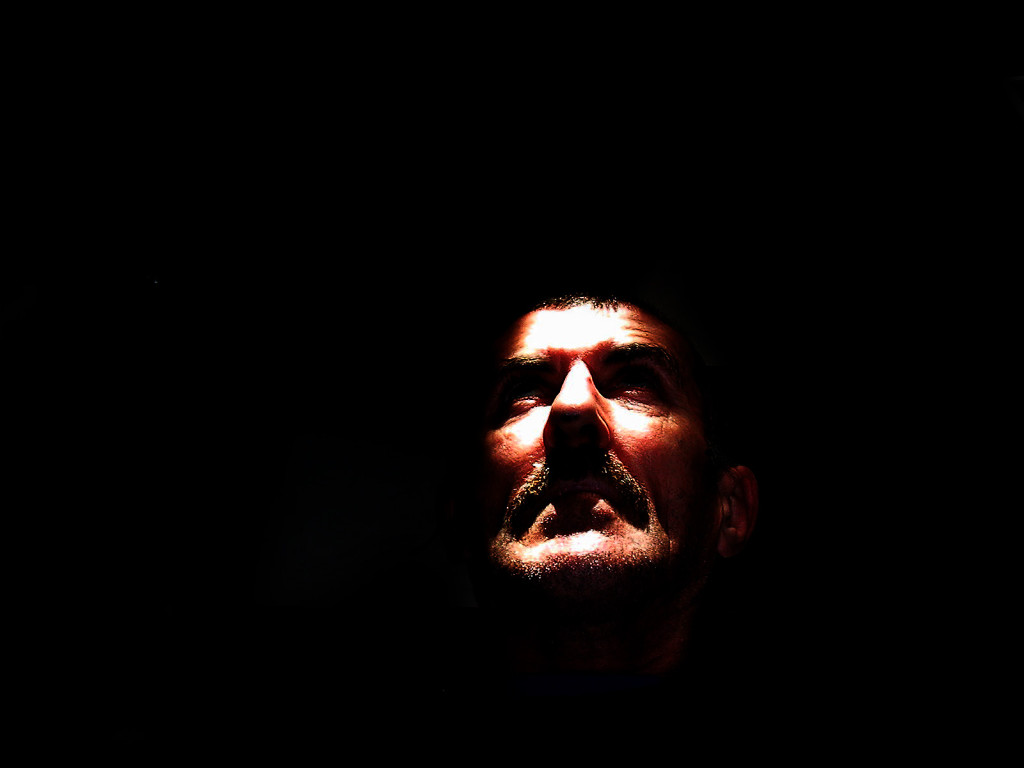

Shimon had to go into hiding. No place was safe. That is how he and his son, R. El`azar wound up in a cave. It was no joke. It was a miracle.

They stayed together in the cave for twelve years, never leaving it to see the light of day. In the darkness, over the years, their eyes tried to adjust, but they could hardly see a thing.

They heard the sound of a brook and realized that somehow a spring of water had arrived to sustain them. In the darkness, stretching out their hands, they discovered that a carob tree had grown up to give them something to eat.

Stretching out their hands they could touch each other’s face and feel the wrinkles and cracks grow and deepen over the years. Would they ever be able to see the light again?

And in the darkness, just the two of them, father and son studied Torah, remembering and innovating, transmitting and creating a Tree of Life, buried in a hole in the earth.

One day, after twelve years like this, they heard the voice of Elijah the prophet calling out: “The danger is over. The Roman emperor is dead and his decree is annulled. Bar Yohai is safe.”

So father and son slowly crept out of the cave – the grave that had been their Eden, and crawled into the open. The sun was shining; it was a glorious day. Shielding their eyes from the blinding glare, they scanned the landscape and saw a man peacefully tilling his field. A Jewish farmer, working in peace! What a sight for sore eyes!

But these cavemen saw things in a different light. Rashbi was as consumed with outrage now as he was in his discussion with his colleagues, years earlier. “How can this man neglect the treasures of the Torah and put his efforts into ploughing the earth? He throws away eternal life for an existence that depends on the whims of the seasons!” His eyes, which had not beheld a thing in twelve years of darkness, shot forth bolts of fire that destroyed the field and set the farmer to flight.

Distilled and concentrated over the years, shielded from exposure to the “primes” of a corrupt environment, Rashbi’s protest against any deviation from complete purity of soul knew no bounds. His radical critique of society had no room for basic compassion and acceptance of the ways and limitations of others.

Immediately a Heavenly Voice was heard: “Is this how you use the holy strength that you have amassed all these years. Have I preserved you in order for you to destroy My world? Go back into the cave and learn your lesson!”

And Rashbi and his son, R. El`azar, had to return to the cave, to the darkness.

It was a punishment, but it was also a return to a world that they had come to know best, a world that they had hallowed with their simple living and their single-minded devotion.

So they would return to studying the Torah together. But now they had to study with a new consciousness.

Before, they were immersed in a world outside time, an eternal world. But now they knew that they were entering a temporary world, for only a season.

This time they knew that they were destined to emerge from their limited but perfect home into the outside world.

How should they engage in their studies in a way that would prepare them to leave their closed paradise and live in that expansive but imperfect world we are meant to inhabit?

Later generations imagined that the two sages imbibed hidden secrets of Torah. But the story does not tell us.

What it does tell us is that Rashbi and his son reemerged from the cave a year later. Had they changed? Had they learned their lesson? Not completely, says the Talmud. R. El`azar was still incapable of making peace with the flawed environment he encountered. Everywhere he looked, his eyes shot out flames of destruction.

But Rashbi had learned. He had become transformed. Everywhere that R. El`azar gazed and destroyed, Rashbi gazed again and restored and healed. They slowly walked along, the younger rabbi struggling to learn from his father what he had failed to learn in his thirteen years of cloistered apprenticeship in the cave.

Rashbi looked at his own son, whose face he could not look at in the darkness, and saw only goodness and promise.

It was Friday afternoon. The sun was setting and Shabbat would soon begin. They saw an old man who, for all his age, was rushing along, two bundles of myrtles in his two hands.

They called out to him: “Elder, what are you carrying those for?”

He answered: “They are to honor the Shabbat.”

“But why do you have two bundles?” they asked. “One bundle looks quite sufficient.”

“One is for the commandment, ‘Zakhor’ – to remember to make the Shabbat holy, and one bundle is for the commandment, ‘shamor’ – to protect and preserve the Shabbat, for she is precious and fragile.”

To put this in Professor Kahneman’s phraseology, the old man was carrying reminders, “primes” that would affect him, consciously and subliminally, to hold on to a different set of values than those constructed by the empire all around him.

Only then did Rashbi and his son both make peace with our world. Rashbi pondered what he had experienced and he said to his son: “We did not come here to use our holiness and righteousness to destroy. Let’s go see what we can do to repair this world.”

So Rashbi returned to civilization. He entered the city and saw the magnificent market places, the baths, the bridges. And he saw how these projects were grand, but were also spreading without a thought for basic human values or for the distinctive way of life of his people. A road was constructed impressively, but it was planned without consideration for the cemetery that was in its way.

So he dedicated his considerable knowledge and passion to find ways to “remember – zakhor’ and to “protect – shamor’ the values of holiness and purity of our tradition so that they might continue to prime us while we engage in constructing this world.

Yehudah apologized for a corrupt system and was coopted by it. R. Yose was silent. His way led to exile. R. Shimon bar Yohai resisted and protested. His way was fraught with risk. He made mistakes. But he is the one who, with his son, grew in wisdom and holiness, and found a way to be effective in this world.

Whose path shall we choose for ourselves?

Shabbat Shalom u-g’mar hatimah tovah – May we enjoy a Shabbat of peace, and may we be finally confirmed for a good year!

Rabbi Greenstein

Image: “IN THE LIGHT OF DARKNESS” by aka Tman is licensed under CC BY 2.0

- Toby Stein: In Memoriam - Thu, Feb 8, 2024

- Faithfulness and Hope: Parashat Sh’lach - Thu, Jun 23, 2022

- Past Their Prime: Parashat B’ha`a lot’kha - Thu, Jun 16, 2022