Parashat Sh’mot

Exodus 1:1 – 6:1

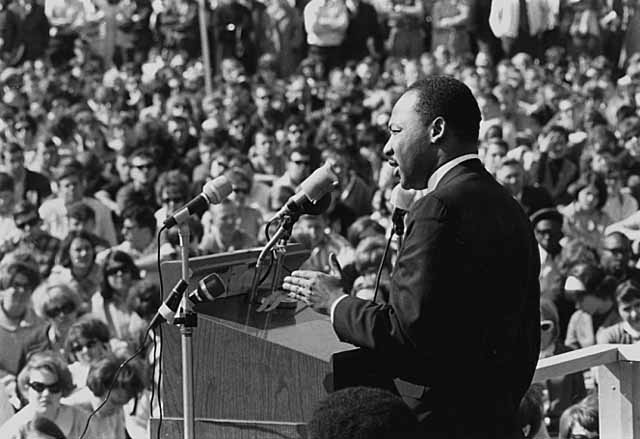

A review of the Torah portion for this Shabbat, in between the day that commemorates the great Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the day in which the inauguration of a new President of the United States will occur, stirs up questions about national leaders and leadership. Leaders are often blessed with certain talents and gifts that make them special. But part of their stature derives, not from how they are exceptional, but, rather, in that they are reflective of the people they are trying to lead. In some sense they function as representations of certain qualities or hopes of their people.

Our Torah portion presents us with two new national leaders. A new Pharaoh leads Egypt. His name is the hereditary title of the Egyptian ruler. He apparently comes by his leadership position through the workings of the system, perhaps through heredity, perhaps through a struggle among powerful elites. His authority is unquestioned by his people or anyone else. Pharaoh does not worry that his own people may not accept his rule, no matter what policies he may pursue. His only worry is about the “outsiders”, the Hebrews. Moses is the leader of the Hebrews. His ascent to leadership is more complicated. He does not become his people’s leader through their choice. Indeed, although he is appointed by God, he has serious doubts about whether the Hebrews will accept him.

This raises an intriguing question. What has happened to the Hebrews so that they lack a recognized leader? Our Torah portion tells us that “a new Pharaoh arose over Egypt who did not know Joseph.” (Ex. 1:8) Clearly we are meant to see the injustice in this leader’s willful refusal to acknowledge the immense contributions of Joseph to saving Egypt. But it also tells us that there has been no successor after Joseph to lead the Israelite people. Where are the leaders?

And this question points to another problem: Our story begins by portraying a thriving, growing Hebrew people. They are not yet enslaved. Why have they not returned to their own homeland? Here is where the interdependence between the people and their leaders comes into play. Perhaps the Hebrews did not return to the Promised Land because they lacked leaders to move them forward. And perhaps they lacked such leaders because they had lost their own desire to fulfill that dream of return. Perhaps they chose not to follow leaders who pointed the way.

Cynics say that we always get the leaders we deserve. But the Torah tells a more complex story. The Egyptians, who had no choice in designating their leader, did not deserve their Pharaoh, nor the suffering he brought upon them. People do not deserve the leaders that are imposed upon them through authoritarian regimes. But what about societies and peoples that can choose their leaders? The Torah shows us that Moses did not become the Hebrews’ leader because he had been chosen by the people. Still, even God acknowledges Moses’ argument that, though he is God’s chosen agent, Moses must still gain the people’s acceptance. So did the Israelites really deserve such an amazing leader as Moses? There is a strong voice in our tradition that teaches that, just as the Egyptians did not deserve their Pharaoh, the Israelites did not deserve Moses.

Sometimes, whether we deserve it or not, we are sent leaders called by a Divine voice. Moses was such a one. Somehow, the people of Israel eventually succeeded in accepting his leadership. The Reverend Dr. King was also such a one. His tragic fate, on the other hand, is our own eternal loss and failure. But the power to choose our leaders says the Torah, is not exercised only for a moment. It is a power we wield continuously. We are neither Pharaoh’s subjects nor his slaves. We are the people of Moses, whose God-given authority was still dependent on our own acceptance. If we were undeserving yesterday, we can strive to become deserving today. And, as Americans, despite our past failings, it is still in our power, today, to decide whether to accept Reverend King’s leadership and vision. May we be worthy custodians of that power.

Shabbat Shalom

Rabbi David Greenstein

Rabbi Greenstein also has a dvar Torah for this week in the Golda Och Academy newsletter.

![]()

Subscribe to Rabbi Greenstein’s weekly d’var Torah

image: “King speaks at an anti-Vietnam War rally at the University of Minnesota, St. Paul (1967)” © Minnesota Historical Society, photographer uncredited, altered and used with permission via Creative Commons License

- Toby Stein: In Memoriam - Thu, Feb 8, 2024

- Faithfulness and Hope: Parashat Sh’lach - Thu, Jun 23, 2022

- Past Their Prime: Parashat B’ha`a lot’kha - Thu, Jun 16, 2022