Parashat Tazri`a/M’tzora

Leviticus 12:1-15:33

The affliction of surfaces – of our homes, garments and very skin (tzara`at)- that is the main subject of our Torah reading has been interpreted by our tradition to be a signal to us to heed how powerful our gift of speech is and to be aware of how easily we casually debase it as a means to hurt others. This unique, heaven-sent affliction was seen not as a disease, but as a Divine punishment for one who has abused their power of speech to attack others in secret.

Words can cause pain. Usually we think of this with regard to hate speech or even thoughtless rumor-mongering. But our tradition teaches us that this power to hurt inheres in speech itself, and can be true even when the words we utter are words of truth and even necessary truths. Thus, we find recorded in the Mishnah this very poignant disagreement between two sages:

Rabbi Meir says: We examine afflictions [during the intermediate days of the festival] in order to be permissive, but not in order to be stringent. And the Sages say: Neither to be lenient nor to be stringent. (BT Mo`ed Qatan 7a)

This discussion refers to the priest’s examination of the skin afflictions described in our Torah reading. It is the responsibility of the priest to examine a person who has scaly skin sores and, based on his visual examination, the priest has the power to declare the affliction ritually pure (- not tzara`at) or impure (tzara`at). The Mishnah considers whether such an examination should take place during the intermediate days of a festival, when we are called upon to rejoice in our holidays.

The Mishnah realizes that, should the priest examine a person and declare them to be afflicted with this mysterious Biblical rash, they will be rendered ritually impure and their joy will be destroyed, for they will have to leave their home and go outside the camp, into quarantine. So, is the priest’s obligation (to make this determination) of primary importance, or should it be delayed or deferred for the sake of fostering happiness during the holiday?

Rabbi Meir says that the priest must meet their obligation to see the afflicted person. But the priest can still be selective in whether to utter their pronouncement. If they can discern that the person is not afflicted with tzara`at, they may say so. In fact, this will increase the person’s joy, for their worries will be dispelled. But if the priest sees that the affliction is, indeed, tzara`at, the priest can delay pronouncing those determinative words until after the holiday concludes. For now the priest should remain silent.

But the Sages disagree. It is better, they argue, for the priest to remain silent altogether. One way to understand their position is to say that the Sages believe that, once the priest has finished their examination and knows what the facts are, the priest has no right to withhold the diagnosis, no matter how painful it might be to accept. Therefore, they say, it is better to postpone the appointment completely until after the holiday. (Another possibility is that they realize that even though the bad diagnosis has been postponed, the person will understand the implication of such a postponement, and their holiday joy will be ruined anyway.)

Both sides agree that the priest is discharging a sacred duty by speaking the truth about the afflicted person’s condition. And both sides recognize and agree on the hard truth that the words of the priest will cause pain. The only disagreement is whether to postpone the causation of pain until later. The Sages argue for a temporary delay. Rabbi Meir suggests a different compromise. Yet everyone must acknowledge that there is no final escape from the power of speech to hurt, even – or especially – in pursuit of the cause of truth.

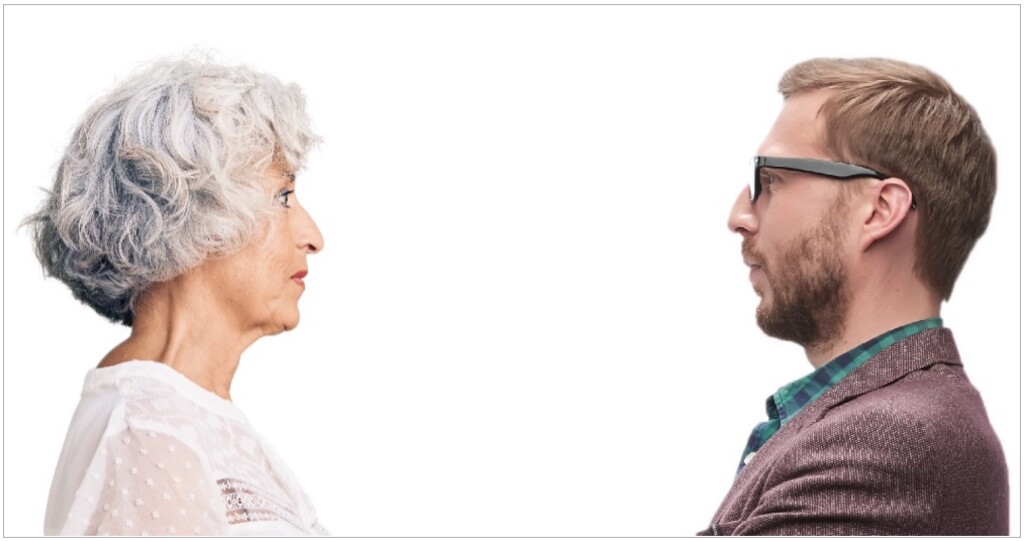

What is the difference between the hurt caused by the shrewd tale-bearer and the harm caused by the upright priest? The superficial similarity between the two is connected to the superficial affliction that may – or may not – be tzara`at. They seem to be the same, but, under close examination, they are not. The pain caused by the slanderer and gossiper is meant to be permanent and irrevocable. It is meant to serve the corrupted soul of the speaker, who thinks they will feel better through the pain and humiliation secretly caused to the other. But the pain caused by the priest is meant to be only temporary and for the sake of the afflicted person. The speech of the priest – spoken face-to-face to the afflicted – is meant to aid that person by impelling them toward self-reflection, a process that will wean them away from their insensitive use of speech that diminishes others.

The truth can hurt. But, whether regarding an individual or a society or a nation, the obligation to examine our afflictions and diagnose them remains. That obligation may, under certain special circumstances, be temporarily delayed. But the delay cannot be forever. Eventually the obligation must be met. We may only hope that, if the truth is spoken face-to-face and with genuine concern for the welfare of the person, society or nation addressed, it may yet be a source of healing instead of affliction.

Shabbat Shalom

Rabbi David Greenstein

Subscribe to Rabbi Greenstein’s weekly d’var Torah

Photo: collage of commercial stock images

Thank you to John Lasiter for suggesting the title and selecting an image for this Torah Sparks – Rabbi Greenstein

- Toby Stein: In Memoriam - Thu, Feb 8, 2024

- Faithfulness and Hope: Parashat Sh’lach - Thu, Jun 23, 2022

- Past Their Prime: Parashat B’ha`a lot’kha - Thu, Jun 16, 2022