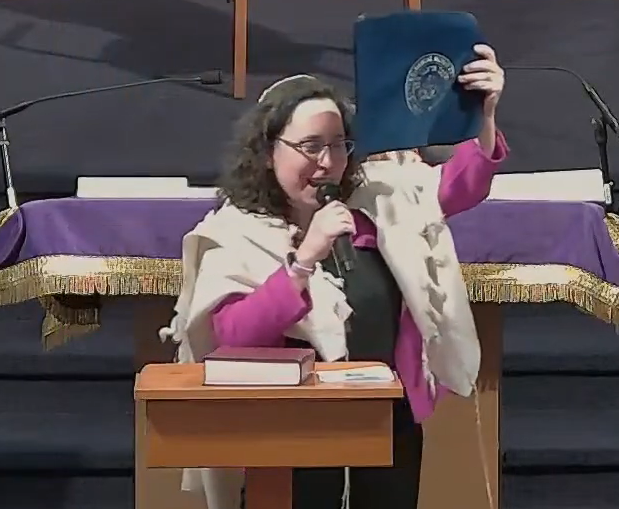

Rabbi Julie’s Parashah Intro

Rabbi Julie’s Sermon

Text of Rabbi Julie’s Sermon: “The First Case of Civil Disobedience”

In this morning’s Torah portion, we read of the first act of civil disobedience in recorded history.

On the Civil Rights trip, we met with the youngest person to march from Selma to Montgomery in the Voting Rights March of 1965. These are their stories.

“A new king arose over Egypt who did not know Joseph. And he said to his people, ‘Look, the Israelite people are much too numerous for us.’ ” (Ex. 1:8-9). So, Pharaoh enslaved our ancestors, setting task masters over them and oppressed them with forced labor ruthlessly. But the more they oppressed, the more we grew.

In response to his fear and out of an inability to see our ancestors as full human beings, the king of Egypt announced an evil decree:

“The King of Egypt spoke to the Hebrew midwives, one of whom was named Shifra and the other Puah, “saying, when you deliver the Hebrew women, look at the birthstool: if it is a boy, kill him; if it is a girl, let her live. The midwives, fearing God, did not do as the king of Egypt had told them; they let the boys live.” (Ex. 1:15-19).

* * *

In her book, Turning 15 on the Road to Freedom, Lynda Blackmon Lowery opens, “By the time I was fifteen years old, I had been in jail nine times.” (p.13)

It’s hard to describe in words what it was like to hear Lynda tell us her story. She had a quiet fire about her, a gentleness and a fierceness, a sense of humor and a haunting refrain of trauma, that are hard to fully capture. She captivated us with her story, but even more so with her determination and open heart, her scars and her triumph.

Lynda writes in her memoir, “It was my grandmother who first took me to hear Dr. King…when I was just thirteen years old. The church was packed. When Dr. King began to speak, everyone got real quiet. The way he sounded made you want to do what he was talking about. He was talking about voting – the right to vote and what it would take for our parents to get it. He was talking about nonviolence and how you could persuade people to do things your way with steady, loving confrontation. I’ll never forget those words – “steady, loving confrontation” – and the way he said them. We children didn’t really understand what he was talking about, but we wanted to do what he was saying.” (p.21-22)

* * *

Rabbi Al Axelrod was the Hillel Director at Brandeis University in the 1960’s. He established an award for non-violent resistance to tyranny which he named the Shifra and Puah award, after the Hebrew midwives who resisted and outsmarted Pharoah and saved the infant boys from drowning.

Rabbi Axelrod takes note that the midwives are mentioned by name, something that is unusual for women in the Torah. He said, it is “not a mere accident that the Hebrew Bible sees fit to preserve the midwives’ names. They came from nowhere, are introduced abruptly in the text and are not heard from later. Yet, their singularly courageous act merits their being mentioned by name if only in one verse.”

“It is time”, he urged, to recoup for Shifra and Puah, and for the noble tradition of civil disobedience…their rightful place of prominence in Judaism.”* * *

On the first morning of our trip, before attending church services at the Ebenezer Baptist Church we visited the King Center where the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and his wife Loretta Scott King are buried. Their caskets are in the middle of a large fountain, where water cascades down a series of steps that are inscribed with these famous words that I remember a little differently. Instead of saying, let justice roll down like water, and righteousness like a mighty stream, the memorial reads, “we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like water and righteousness like a mighty stream.”

Before the trip I thought I already understood the commitment to nonviolence during the Civil Rights movement. I knew it was a philosophical choice, but I also understood civil disobedience as primarily a tactical choice. Yes, it required courage in the face of violence, but as I heard about and read about the trainings that activists underwent, the ways they practiced being threatened and attacked and not only not getting angry, or striking back, but also not turning away, I realized how very difficult nonviolence is as a spiritual discipline.

At the King Center, there is a monument, steps away from the tomb, dedicated to King’s philosophy of nonviolence. On one of the stone tablets, these words from Coretta Scott King are inscribed, “People who think nonviolence is easy don’t realize that it’s a spiritual discipline that requires a great deal of strength, growth, and purging of the self so that one can overcome almost any obstacle for the good of all without being concerned with one’s own welfare.”

There is an image from a black and white photo I saw in one of the museums we visited, of a young girl extending her hands behind her as she is beaten by a Billy Club. The gesture is so striking it is the opposite of our instinct to protect ourselves or to fight back. It captures for me the key principals of nonviolence that are inscribed at the memorial in Atlanta, taken from Dr. King’s first book, Stride Toward Freedom.

Nonviolence is a way of life for courageous people.

Nonviolence seeks to win friendship and understanding.

Nonviolence seeks to defeat injustice, not people.

Nonviolence chooses love not hate.

Nonviolence believes the universe is on the side of justice.

Of all the things I learned about nonviolence during my trip, the one that sticks with me the most is the idea that the protestors strived not only for nonviolence, but even for love. Dr. King’s highest ideal was to maintain love in one’s heart even in the face of hatred and violence. Not just love in general, but even love for the person who was shouting slurs or even beating you.

* * *

Civil disobedience at its essence is an act of moral conscience when we break an unjust law in answer to a higher moral calling. The Torah teaches, that “the midwives, fearing God, did not do as the king of Egypt had told them; they let the boys live.” Their reverence for God was inextricably linked to a reverence for all human life. Their fear of Pharaoh and the mortal risk they were taking by ignoring his decree, was overcome by their fear of Heaven, by the fear of living in a world where new-born babies were killed.

In the words of Rabbi Susan Niditch in Torah: A Women’s Commentary, “these women understood instinctively that Pharaoh should be disobeyed; and, with initiative, they acted on this knowledge… Thus, from these women filled with a power rooted in moral reason and ethical concern for life, and the capacity to empathize, we learn a valuable lesson in political ethics: the very weakest in society can contribute to liberation by judiciously engaging in acts of civil disobedience.” (p.324)

And when the tradition says that Shifra and Puah let the baby boys live, this is understood not as a passive action, but something they did actively. Rashi, the famous medieval commentator says, “rather they made them live – by providing them with food. And his grandson Rashbam adds, “rather they made them live with all their might, even more than they would have done had there been no decree at all. This must be the meaning of the words, for the verse has already told us that [the midwives] disobeyed the king’s instructions not to kill the boys.

Here, our tradition is teaching that civil disobedience isn’t simply refraining from taking an action that is reprehensible, but actively taking steps to reverse an evil decree.

* * *

As a teenager in Selma, Lynda recalled the experience of marching and being repeatedly arrested. They would be in school, she told us, and the teachers would unlock the back door so they could sneak out while the teachers were busy writing on the chalkboard. At first, the students would march for four or five blocks and then board yellow school buses. She recounts, “if you didn’t get on the bus fast enough, the police would shock you with a cattle prod”. (p.28)

But as the protests continued, the violence intensified. Lynda was on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma on that fateful Bloody Sunday when the Alabama State troopers violently attacked the marchers. She was beaten so badly she had to be taken to the hospital to stop the bleeding.

When the march from Selma to Montgomery was planned, Lynda was determined to march the fifty miles to the State capital to show Governor Wallace that she would not be stopped by what happened to her. When Lynda told her father she wanted to go, he said no. “It would be too dangerous. But [she] begged” and told him “he’d have to tie [her] up and lock [her] in the house to keep her from going.” (p.63)

In her memoir, Lynda recalls that “after about five or six miles, most of the three thousand marchers had to go back to Selma. Only three hundred of us were permitted to march all the way to Montgomery. Of the marchers going the whole distance, I was the youngest of them all…I was just one day short of my fifteenth birthday” (p.74)

* * *

There was another act of courage that we sometimes overlook in the story of the midwives, the courage it took for our Israelite ancestors to become pregnant in the first place. According to the midrash, Shifra was Yocheved, Moses’ mother, and Puah was Miriam. Miriam was called Puah because she had rebuked her father, as the Hebrews for rebuke, hofi’ah panim, sound like Puah. Amram, her father was a communal leader and when Pharoah decreed that Israelite boys would be cast in the Nile, he stopped having intimate relations with his wife, and even divorced her. Our tradition imagines it would have simply been too painful to give father a child, risking that it would be a boy. Following his example, all of the Israelite men divorced their wives. According to the midrash, Miriam stood up to him and said, “Father, your decree is harsher than that of Pharaoh. He only decreed against the males, but you have decreed against the males and females.”

Miriam succeeded in convincing her father to return to Yocheved and all the Israelite men to return to their wives.

This midrash teaches us that it’s not only the midwives who exercised courage in the face of tyranny but also the parents who conceived and raised children in times of oppression.

Even though Lynda’s father didn’t want her to participate in the march for voting rights because he feared it was too dangerous, he and his wife had the courage and the hope to bring Lynda into the world, even though they were living through segregation in the Jim Crow South.

* * *

Of all the stories Lynda told us that day in Selma, the most moving one was the first. She told us that she first got involved in the Civil Rights movement on September 19,1957, the day her mother died of childbirth complications. Lynda was seven years old. She lost a lot of blood as a result of hemorrhaging following the birth of her fourth child. Lynda’s mother needed a blood transfusion, but in the Jim Crow South she couldn’t get treatment or blood from a nearby white hospital. Instead, blood was sent from Birmingham to Selma on a Trailways bus, a distance of 90 miles. By the time the blood arrived at the infirmary for colored people where Lynda’s mother was being treated, she had been dead for fifteen minutes.

It was because of those 15 minutes that Lynda found the courage to march, to go to jail, to be beaten and to march again. It was because of those 15 minutes that Lynda continues to tell her story today.

* * *

I remember thinking at the time that 15 minutes is about the time it takes to bake matzah, the unleavened bread we eat to celebrate our redemption from slavery in Egypt. That 15 minutes that cost Lynda’s mother her life inspired her to follow Dr. King’s words, even though she didn’t fully understand them when she first heard them at age 13. “Steady, loving confrontation”. Blacks wouldn’t have voting rights in this country if not for people like Lynda. And the Jewish people wouldn’t be alive today, if not for people like Shifra and Puah. In Lynda’s words, “we were determined to do something, and we did it. If you are determined, you can overcome your fears, and then you can change the world. (p. 102)

Video Archive

Livestreams and an archive of all Shomrei videos is available on our YouTube Channel at shomrei.org/video

- Shabbat Your Way Message From Rabbi Julie - Wed, Apr 17, 2024

- Parashat Vayikra – 3/23/24 - Thu, Mar 28, 2024

- Shabbat Your Way Message From Rabbi Julie - Thu, Mar 14, 2024