Notes from the Lampert Library

Notes from the Lampert Library

Sometimes a book tells an inspiring story. The recently published When Books Went to War: the stories that helped us win World War II by Molly Guptill Manning is one of those. Ms Manning, a lawyer by trade, posits that books helped the soldiers through hard times in battle and beyond, made the hours of waiting for the unknown bearable, and instilled values and brought education to millions of young soldiers. In a way, books helped win World War II.

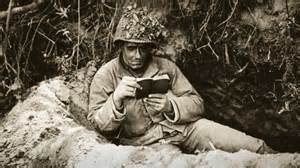

Comparing the book burnings in Hitler’s Germany to the massive efforts to send books to the troops in both the European and Pacific theaters, Manning quotes often poignant letters from soldiers in lying in foxholes near battlefields, recuperating in hospitals, and in transit to battlefields expressing how important the books were.

“Books are weapons in the world of ideas,” stated the Council on Books in Wartime. The Council felt that “the mightiest single weapon this war employed was not a plane or a bomb or a juggernaut of tanks. It was Mein Kampf. “According to the author, Germany destroyed an estimated 100 million books. Ten thousand authors were banned in Germany and German occupied countries. The specially printed US Armed Forces editions of books numbered more than 120 million and countered German book burnings.

In 1934, HG Wells, as a protest against the burning of books, formed the Library of Burned Books in Paris. Ironically, this collection was retained by the Germans when they conquered Paris. Time Magazine coined the word bibliocaust to describe the bonfires of books in squares all across Germany and later in German held countries.

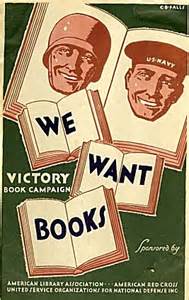

After the United States entered the war, a call went out for books for soldiers. The Victory Book Campaign collected millions of books donated by individuals, libraries, and publishing companies. While well intentioned, in reality the campaign missed the mark. Many of the books were unsuitable for young men in their late teens and early twenties. Certainly the size and weight of many volumes were impractical for shoving in a backpack or uniform pocket or reading in a foxhole.

After the United States entered the war, a call went out for books for soldiers. The Victory Book Campaign collected millions of books donated by individuals, libraries, and publishing companies. While well intentioned, in reality the campaign missed the mark. Many of the books were unsuitable for young men in their late teens and early twenties. Certainly the size and weight of many volumes were impractical for shoving in a backpack or uniform pocket or reading in a foxhole.

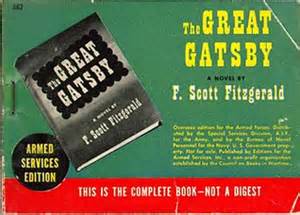

After seeing how well used base libraries were, the Army realized how important putting suitable reading material in the hands of the young American troops was- especially in this war of ideologies. The Army’s chief librarian Raymond L. Trautman, along with publishers and the American Library Association, designed the Armed Forces Editions (ASE), specially printed and sized editions of bestsellers, classics, how-tos and other genres meant to appeal to a wide range of readers and perfect for shoving in a uniform pocket.

After seeing how well used base libraries were, the Army realized how important putting suitable reading material in the hands of the young American troops was- especially in this war of ideologies. The Army’s chief librarian Raymond L. Trautman, along with publishers and the American Library Association, designed the Armed Forces Editions (ASE), specially printed and sized editions of bestsellers, classics, how-tos and other genres meant to appeal to a wide range of readers and perfect for shoving in a uniform pocket.

Ironically the first book printed in an ASE was The Education of Hyman Kaplan, written by a Jew. Over the course of several years, a carefully curated collection of 1300 titles chosen for a wide variety of interests was published. These books were traded among the troops, taken to POW camps, and even became souvenirs. Censorship was minor with the guidelines stating that just about anything was suitable except for books that might “give aid and comfort to the enemy, conflict with the spirit of American democracy, be offensive to any religion or racial group, trade or profession.”

A favorite book was A Tree Grows in Brooklyn; the ASE campaign made The Great Gatsby a best seller; and the ASEs made lifelong readers of millions of men and inspired many to pursue their educations through the GI Bill.

A favorite book was A Tree Grows in Brooklyn; the ASE campaign made The Great Gatsby a best seller; and the ASEs made lifelong readers of millions of men and inspired many to pursue their educations through the GI Bill.

Today when the future of the printed book is being debated, it is staggering to remember the power that books had in keeping the connection to home and contributing to the positive morale that was needed to maintain a fighting spirit and win the war.

- Is It Passover Yet? - Thu, Apr 18, 2024

- MESH Report April 9, 2024 - Thu, Apr 11, 2024

- Guess Who? - Wed, Mar 13, 2024